By Nichola Shackleton –

Obesity, a key public health issue for the 21st century and possibly one of the most talked about and researched health topics. But it’s more than a health condition; there are social and economic consequences to obesity also. Obesity is visibly different to society’s idealisation of ‘thin or fit’ bodies, therefore it is stigmatised. Obesity is also a matter of industry and economics, as changes in food production, affordability, availability and marketing have their role to play in increasing consumption. Childhood obesity is a key issue for policy makers, not just because of the impact it has on individuals, but also because of the costs to treat the health conditions and disabilities it causes. As child obesity tends to lead to adult obesity, and health problems magnify the longer a person remains obese, researchers have started to focus on child obesity at younger ages.

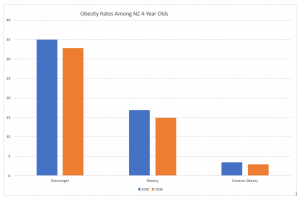

We have some good news: Child obesity rates among 4-year-old children in New Zealand are declining. They are declining for boys and girls of all ethnic groups, and for all levels of deprivation.

Using data from 84% of the population of 4-year olds in New Zealand from July 2010 to June 2016 we found declining trends in child obesity across all segments of the population.

Overall, overweight decreased from 35.0% to 32.8%, obesity from 16.9% to 14.9% and extreme obesity from 3.5% to 2.9%. On average overweight prevalence rates decreased by about 1% per year, obesity prevalence rates by about 2% per year and extreme obesity by about 4% per year. To be sure the trends were not being driven by the changing demographics in the population, we used models which took into account increases in the number of children living in urban areas, increases in the number of children of Asian ethnicity and changes in the distribution of children across the deprivation spectrum over the 6 year period. These downward trends remained.

|

‘Even if overweight and obesity levels are declining, or are stable, for the population as a whole, this is not the case for the more deprived segments of the population’ |

While this appears to be fantastic news, research from overseas repeatedly shows that even if overweight and obesity levels are declining, or are stable, for the population as a whole, this is not the case for the more deprived segments of the population. Therefore we considered whether the rates of overweight and obesity were declining for boys and girls, for children of different ethnicities, and for children experiencing different levels of deprivation.

More boys were overweight and obese than girls but rates decreased for both boys and girls over time. Rates of overweight and obesity differed by ethnicity, but rates decreased across all ethnic groups over the 6 year period, and while rates of overweight and obesity were consistently over twice as high for children living in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived areas, rates of overweight and obesity decreased across deprivation groups.

We investigated the relationship between deprivation and ethnicity jointly and found a stronger relationship between deprivation and obesity for Māori and Pacific children. But within ethnic groups the strength of the relationship between deprivation and obesity remained the same across the 6 years.

While this is a good news story, there is still a lot of work to do. Overseas research indicates that even if child obesity trends are declining in preschool-aged children, this is not translating to decreases once children are in school. In New Zealand we have no national screen of child health and development once children enter school and so we know little about the growth and development of school-aged children. Given that children spend a large amount of time in school, this seems like a natural place to intervene and work on improving and promoting healthy food environments, eating habits and activities. Yet, for such interventions to be funded, there needs to be evidence – evidence outlining the nature of the problem regarding the transition to school, and a way to evaluate changes over time and the impact of school based/population level interventions.

| ‘There needs to be evidence… and a way to evaluate changes over time and the impact of school based/population level interventions’ |

Nichola Shackleton is a COMPASS Research Fellow at the University of Auckland who works on the Better Start National Science Challenge